More Stories

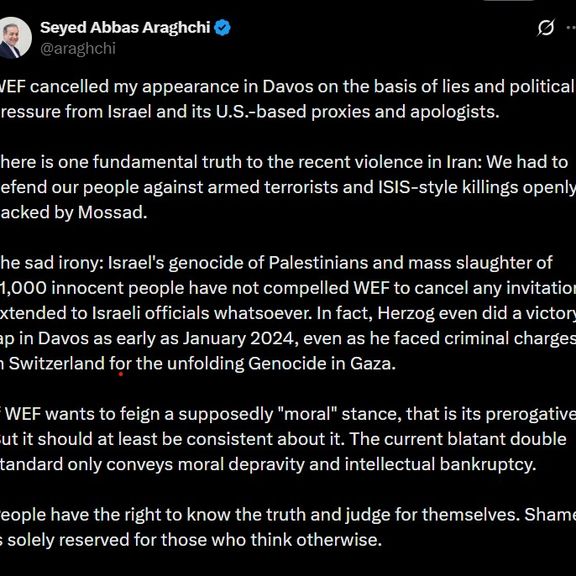

Iran’s foreign minister Abbas Araghchi said on Monday the World Economic Forum cancelled his planned appearance at its annual meeting in Davos due to what he described as political pressure from Israel and its "proxies" in the United States.

“The World Economic Forum cancelled my appearance in Davos on the basis of lies and political pressure from Israel and its United States-based proxies and apologists,” he said in a post on X.

“There is one fundamental truth to the recent violence in Iran: We had to defend our people against armed terrorists and ISIS-style killings openly backed by Mossad,” Araghchi added.

The Islamic Republic's resort to the deadliest crackdown on protestors in its history signals endgame for the theocracy, retired US Army General and ex-CIA director David Petraeus told Iran International Insight, the channel's town hall held in Washington DC.

“This regime is dying. Essentially it’s fighting, it’s killing again, but it is also dying," said Petraeus, a retired four-star Army general who now runs the Middle East business of US private equity firm KKR.

“I think it signals enormous questions about the regime's ability to sustain the situation,” he said, arguing Tehran is under more pressure now than at almost any point since the Iran-Iraq war.

Speaking to host Farzin Nadimi, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute, Petraeus painted a stark picture of the clerical establishment facing simultaneous existential challenges at home and abroad.

“Iran is essentially defenseless at this point,” Petraeus said, referring to the destruction of air and ballistic missile defense systems early in a June conflict with Israel and the United States.

The veteran commander, who led the so-called "surge" of US forces aimed at defeating an insurgency at the height of the US war in Iraq, said the scale of violence used against demonstrators reflects fear rather than control by Iran's leaders.

While he acknowledged the Islamic Republic may be able to suppress unrest in the short term, he warned that flooding cities and towns with security forces may not buy authorities a lasting reprieve from popular anger.

“This regime has lost legitimacy. The problem is it hasn’t lost the capability to kill.”

His assessment comes as Iran grapples with sustained nationwide unrest that began on December 28 among electronics and cellphone merchants at Tehran’s bazaar and quickly escalated into a nationwide uprising against the Islamic Republic.

At least 12,000 people were killed in just two days, according to medics and Iranian officials speaking to Iran International.

With the Iranian currency cratering, inflation climbing and purchasing power collapsing, Petraeus said Iran no longer has the financial tools it once used to calm the streets.

“At this time, there's not much Iran can do about it. They have very little capacity."

Asked about Trump's mooted pledge to intervene militarily to defend protestors, Petraeus stopped short of assessing the efficacy of any US attack but said the move would be well received and not bolster the leadership.

“I think we could take action against the regime and it would be applauded … not be a rallying cry for them.”

The latest wave of protests in Iran once more demonstrated both the depth of popular opposition to the Islamic Republic and the limits of mass mobilization in the absence of a decisive breakdown in the regime’s coercive capacity.

As observed by numerous scholars of revolution, opposition forces are almost never in a strong position to defeat a regime’s armed forces. Revolutions occur when, for whatever reason, those armed forces stop suppressing the opposition.

This can happen for different reasons. One is that personnel within the armed forces simply refuse to carry out orders to suppress the opposition, as occurred in the democratic revolutions in much of Eastern Europe in 1989 and in subsequent “color revolutions” elsewhere.

The Islamic Republic’s armed forces, however, have so far proven quite willing to suppress Iranian citizens.

Another possibility is that the regime is more frightened of its armed forces than of its opponents, and therefore does not allow them to act forcefully for fear that they might seize power after suppressing the opposition.

This is what happened in Iran in 1979. But while Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was unwilling to use force effectively against his opponents, the Islamic Republic has shown no such hesitation.

Yet another scenario is that a split develops within the ranks of an authoritarian regime’s armed forces, with significant elements defecting to the opposition.

A defection by a key commander can quickly cascade, as occurred over just a few days in the Philippines in 1986. When such a defection occurs, the remaining security forces are confronted not merely with suppressing unarmed civilians, but with fighting armed men like themselves—a prospect they often wish to avoid.

This has not yet occurred in Iran, but in my view it remains the likeliest path to bringing down the Islamic Republic.

What would it take for this to happen? Most probably, it would require officers to feel confident that their institution would survive the regime’s downfall and remain intact under a new political order.

The commanders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) are less likely to feel such confidence than Iran’s regular armed forces. But even if elements of the regular military were willing to defect to the opposition, they would likely still have to fight the IRGC—unless the latter collapsed when faced with the prospect of confronting the regular army.

These are the fraught calculations confronting those within Iran’s armed forces who share the population’s opposition to the regime.

The Trump administration might be able to affect this calculus through attacks that degrade the IRGC, but not Iran’s regular armed forces.

In other words, for the regular military to risk turning against the regime, it would have to believe both that it could defeat the IRGC and its Basij allies, and that it would itself survive the fall of the Islamic Republic.

Alternatively, some kind of deal would have to be made with IRGC commanders, assuring them of integration into a new regime’s armed forces.

On its face, of course, such an idea is utterly repugnant.

There is also the hope that rank-and-file members of the regime’s armed forces might refuse orders to fire on demonstrators and instead turn their weapons against their commanders and the regime. This, however, does not appear likely.

That being the case, the only viable path to bringing down the regime may be some form of accommodation with key elements of its armed forces.

The Trump administration’s transactional approach to foreign policy might make it more open to attempting this. But America’s authoritarian Arab allies may be even more fearful of a democratic Iran than of a weakened Islamic Republic. The mere existence of a democratic Iran could inspire democratic movements in Arab countries—something their rulers are keen to avoid.

Conservative Israeli governments, too, have long taken a dim view of democratic movements in Muslim countries, which they do not expect to be as accommodating as certain authoritarian Arab governments that have signed the Abraham Accords.

Israel and Iran’s Arab neighbors, in particular, can therefore be expected to lobby the Trump administration about the dangers and unpredictability of political change in Iran.

Unfortunately, all this suggests that without key defections from within Iran’s armed forces—or efforts by the United States or other outside powers to encourage them—the Islamic Republic is more likely than not to remain in power.

The best hope for Iran’s democratic opposition is to secure an accommodation with key elements of the armed forces that would trigger the kind of security-force defections seen in successful democratic revolutions elsewhere.

This is far easier said than done. But where it has happened, it has often come suddenly and unexpectedly.

I sincerely hope this will happen in Iran.

Iran's intelligence agents detained and questioned Omid Ravankhah, head coach of Iran’s national under-23 football team, for several hours on Monday after he arrived in Tehran from Dubai, people familiar with the matter told Iran International.

Intelligence agents confiscated Ravankhah’s passport before allowing him to leave the airport. He was instructed to report to a security body on Tuesday, the people said.

According to the people, Reza Naghipour, the caretaker manager of the national under-23 team, has threatened Ravankhah over his public support for the people of Iran. Naghipour had previously threatened former footballer Ali Karimi with death, they said.

Speaking at a press conference following Iran’s match against Lebanon at the Asian Championship, last Tuesday, Ravankhah voiced explicit support for what he described as the Iranian people’s national revolution against the Islamic Republic.

“It is my social duty, in these circumstances, to stand alongside my people, and no matter what consequences it may have for me, I hope their voices are heard,” he said.

“Unfortunately, for years now in my country, the management of many issues has taken place at the lowest possible level, and people have no right to any form of protest. From here, I want to be the voice of my people, who have endured many hardships in these days,” he added.

Vignettes of horror on Iran's streets were trickling past a state-imposed internet blackout, as eyewitnesses described to Iran International the widespread killing and blinding of protestors with live fire and the denial of medical care to survivors.

Street protests which burst forth on Dec. 28 citing economic grievances quickly morphed into calls for the downfall of the nearly 50-year-old theocracy.

Authorities deployed deadly force to largely quell the unrest in the bloodiest crackdown on demonstrations since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Accounts of the violence which unfolded on Iran's streets at its height on Jan. 8-10 were related to Iran International on Monday and shed light on killing which authorities have acknowledged claimed the lives of thousands but according to medics and government officials total at least 12,000, according to Iran International.

Karaj: wounded protestors shot in Taleghani Square

In Karaj, west of Tehran in north-central Iran, an eyewitness said security forces fired directly at protesters during demonstrations on Jan. 9 in Taleghani Square, killing and wounding a number of people.

The witness said forces deliberately shot dead some wounded protesters and blocked others from reaching hospitals.

Gorgan and Shahin Shahr: snipers on rooftops

In Gorgan, in northeastern Iran, an eyewitness said security forces fired at protesters from the rooftop of Panj Azar Hospital on Jan. 9, adding that a 15-year-old girl was directly targeted and killed.

Separate eyewitness accounts from Shahin Shahr, in Isfahan province in central Iran, said armed forces fired at protesters from the rooftops of public buildings, including a haberdashery bazaar, the education department building, the municipality and the Negarestan building on the nights of Jan. 8 and Jan. 9.

Qazvin: hospitals filled with bodies and wounded

In Qazvin, in northwest Iran, an eyewitness said more than 1,000 people were killed in the city over three nights of protests from Jan. 8 to Jan. 10.

The witness said hospitals were filled with bodies and wounded people within two hours of direct gunfire by security forces on the evening of Jan. 8, adding that the blood on the floors of some medical centers lapped up to exit doors.

Behbahan: eye injuries, machine gun deployment

At least 40 people, and possibly up to 50, suffered eye injuries, a medical worker in Behbahan, in Khuzestan province in southwest Iran, told Iran Iran International. Use of buckshot which has blinded protestors has been reported in previous waves of deadly violence.

The source said vehicles equipped with machine guns were stationed in the city and fired at people on Jan. 8 and Jan. 9.

Hashtgerd: young child shot on sight

In Hashtgerd, west of Tehran in Alborz province, police fired on a family accompanied by a young child on Friday, Jan. 9, a local source told Iran International.

According to the source, a six- or seven-year-old child was seriously injured and suffered heavy bleeding after being hit in the leg by pellets.

The child’s mother said the family was not chanting slogans while leaving their home, but police opened fire as soon as they saw them, according to the source.

Shahroud: protestor shot through the heart

A 31-year-old protester identified as Matin Montazerzohur was killed after being shot by security forces on the evening of Jan. 8 during protests in the city of Shahroud, in northeastern Iran, local sources told Iran International.

Eyewitnesses said he had travelled from Gorgan to Shahroud with friends to take part in the protests and remained in contact with his family until around 8 p.m.

Hours later, his friends informed his family that he had been shot.

The source said the bullet struck him in the chest and ripped through his heart.

His body was returned to his family after four days, on Jan. 12, and transferred to Gorgan. He was buried the following day without a ceremony. Sources said he was self-employed, worked in bodybuilding and had planned to migrate to Turkey.

Isfahan: summonses and pressure on striking shopkeepers

In Isfahan, in central Iran, local sources told Iran International said the Revolutionary Guards intelligence unit summoned shopkeepers who joined strikes and blocked the bank accounts of some of them.