In 2009, many demonstrators chanted “Ya Hossein, Mir Hossein,” framing a disputed election in the language of religious legitimacy and around Mir Hossein Mousavi, a former prime minister who challenged the vote.

Sixteen years later, clips shared from protests and even holiday gatherings at historic sites suggest that a growing share of Iran’s street chant repertoire has shifted to a different refrain: “This is the last battle, Pahlavi will return.”

What unfolded in between is not only a story of anger, but of the shrinking space for incremental change and a widening search for alternatives.

How Iran moved from religiously-coded reformist slogans to open monarchist nostalgia matters for one reason above all: it suggests a growing segment of society no longer sees the Islamic Republic’s internal factions as a route to change.

Act 1: A political arena that emptied out

Official election statistics are contested, but they still illustrate a trend. Authorities said roughly 40 million of about 46 million eligible voters participated in 2009, around 85%.

By July 2024, officialdom reported about 24.5 million votes from roughly 61.5 million eligible voters, or around 40%.

That arithmetic captures a political migration. The eligible population rose by roughly 15.5 million, while the number of participants fell by roughly the same amount.

Whatever the true figures, the gap points to a public that increasingly signals disengagement through abstention – and, at times, through the street.

Act 2: two wings keeping the system airborne

In the mid-2000s, Iran’s political class was roughly divided into a left-right dichotomy. Around that time, a newer identity – “principlism” – took shape on the right.

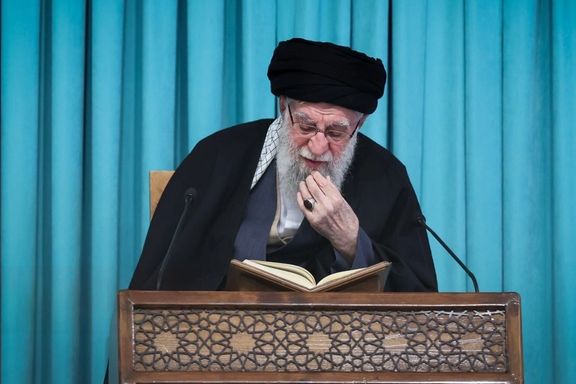

Khamenei, in public remarks, cast the competing camps as two wings with which the country could fly, a formulation many critics interpret as meaning the system could manage dissent by channeling it into controlled competition. He also set out red lines which political discourse could not challenge: the constitution and the revolution’s principles.

After the 2009 protests, Khamenei went further, recalling that he had once told then-President Mohammad Khatami that if a “leftist current” did not exist, he would need to create one – so that the overall outcome of factional rivalry would remain “moderate.”

The subtext was hard to miss: the contest was permissible, even useful, so long as it protected the system.

Act 3: Mousavi – an internal feud packaged as salvation

Many Iranians voted for reformist president Mohammed Khatami in 1997 hoping for gradual reform. Eight years later, that hope had thinned. Officially, Khatami won with more than 20 million votes in 1997; by 2005, the combined votes for the three main reformist candidates were about 10 million.

In 2009, the system’s left wing returned with Mousavi, known as “Imam Khomeini’s prime minister” from the early post-revolution years. The title stemmed from Khomeini’s direct intervention to keep Mousavi in office during the 1980s, overruling then-president Ali Khamenei, who opposed his appointment.

For many young protesters, the title meant little. For the leadership, it carried older grudges. Mousavi’s return also carried a signal to Khamenei: an internal rivalry was being revived.

Mousavi, however, largely kept his challenge inside the Islamic Republic’s own vocabulary – careful not to turn an internal power struggle into a repudiation of the system.

During the campaign he expressed nostalgia for the 1980s – often remembered for repression and war – calling it the revolution’s “golden era.”

In his first statement after the disputed vote, he cast the crisis not as a failure of the Islamic Republic itself but as a betrayal by “untrustworthy custodians” who had weakened what he called “the sacred system,” and he described the protest movement as rooted in religious teachings and devotion to the prophet’s family.

That tension – between street anger and a leadership that still sought legitimacy within the system – was visible even then.

The death of a young female protestor, Neda Agha-Soltan in June 2009 was captured on video and blamed by activists on security forces, becoming a global symbol of the crackdown. But the movement’s most prominent political figure continued to welcome the return of religious slogans as proof of fidelity to the 1979 revolution.

Act 4: The purple interlude

In 2013, Hassan Rouhani entered with a promise to ease sanctions and improve livelihoods. Reformist figures backed him. The Obama administration reached the nuclear deal with Rouhani’s government, and the economy saw partial, temporary relief.

But the political bargain remained fragile. The government pursued subsidy reforms, and in 2016 Donald Trump’s election in the United States shifted the trajectory again. The sense that electoral choices could reliably improve daily life began to erode further.

Act 5: ‘Reformist, principlist – the game is over’

In January 2018, protests that began as economic anger produced a slogan that cut to the core of the “two wings” model: “Reformist, principlist – the game is over.” The chant did not merely condemn one faction; it rejected the system’s entire managed spectrum.

Alongside it came another first in modern protest cycles: open monarchist sentiment, including “Reza Shah, may your soul rest in peace.” He was the founder of the Pahlavi dynasty and served as Shah of Iran from 1925 to 1941.

Act 6: Nostalgia hardens and symbols return

Months later, in spring 2018, a mummified body was reportedly discovered during construction in Rey – near the site of Reza Shah’s former mausoleum, destroyed after the revolution. The episode fueled speculation and fascination, and it landed in a society already primed to argue about the Pahlavi legacy.

Act 7: Bloody November of 2019

The November 2019 fuel-price protests were met with a deadly crackdown that rights groups say killed hundreds. Reformist figures – who had often positioned themselves as aligned with protester grievances – were widely seen as cautious at best, critical at worst.

What stood out in the slogans was not only rejection of Khamenei and the Islamic Republic but a sharper turn toward affirmative alternatives: “Iran has no king, so there’s no accountability,” and “Crown Prince, where are you? Come to our aid.”

Act 8: Woman, Life, Freedom

After a young woman, Mahsa (Jina) Amini, died in morality police custody in 2022, protests erupted nationwide under the rallying cry “Woman, Life, Freedom.” The uprising also expanded the language of protest: chants in local mother tongues spread widely, and debates surfaced more openly among opposition currents.

One new wrinkle was the emergence of anti-monarchy chants – “Neither Shah nor clergy” – in apparent response to the growing visibility of pro-Pahlavi slogans. Other chants expanded the targets to include several left-leaning political currents at once.

Act 9: Nowruz 2025

By Nowruz 2025, videos showed crowds – especially younger people – gathering at historic sites associated with pre-Islamic and national heritage, chanting in support of the Pahlavi family. The geographic spread, from the northeast to Pasargadae, suggested the sentiment was not confined to one city or social niche.

Act 10: Late 2025 and early 2026

In late 2025, the suspicious death of human rights lawyer Khosrow Alikordi in Mashhad drew attention after recordings circulated suggesting he supported the Pahlavis.

At a memorial, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Narges Mohammadi attempted to speak but was met with pro-Pahlavi chants; supporters and critics disputed how representative the chanting crowd was.

Around the same time, the official account linked to Tractor S.C. in Tabriz urged fans to chant in Azeri Turkish against the Pahlavis at matches – an unusual institutional intervention in a politically charged argument.

Then, as Tehran protests began early in January, footage again showed prominent pro-Pahlavi and pro-monarchy slogans.

Chants were even reported at universities, traditionally a center of anti-monarchy politics, showing how far the protest soundscape has shifted.

Accuracy over arithmetic balance

In a race, fairness means everyone starts at the same line; it does not mean the referee forces the same finish. Applied to journalism, the principle is similar: reflect what is most widely heard and most central to the event, without “subsidizing” less prevalent slogans to manufacture balance.

Iran’s protests generate hundreds of chants. No report can list them all. The professional task is to identify what is both meaningfully connected to the protests and demonstrably widespread. Treating a marginal slogan as equal to a dominant one is not neutrality; it is editorial interference – especially in a media environment where a single influencer can rival a legacy newsroom’s reach.

If journalism is to remain relevant, it has to prioritize honest reflection over curated symmetry: equal opportunity for voices to be heard, not equal outcomes engineered on the page.