Five Iranian Christian converts sentenced to stiff prison terms

A seriously ill Iranian Christian convert who broke her spine in Evin Prison is among five Christians handed combined prison terms totaling more than 50 years, a rights group said.

A seriously ill Iranian Christian convert who broke her spine in Evin Prison is among five Christians handed combined prison terms totaling more than 50 years, a rights group said.

The national security offenses for which they were convicted involve house-church worship and Christian activity online, according to UK-based rights groups Article 18.

House-church leader Joseph Shahbazian, his wife Lida, Nasser Navard Gol-Tapeh, another woman whose name has not been disclosed and Aida Najaflou were sentenced, it added.

All except Lida Shahbazian, who received 8 years, were sentenced to 10 years; at least two, including Najaflou, received an additional 5 years for “gathering and collusion.”

Aida Najaflou, 44, fell from her top bunk in the early hours of October 31, fracturing her T12 vertebra. She was taken to Taleghani Hospital for an X-ray but returned to prison the same day on a stretcher, still in severe pain and without the surgery doctors recommended.

Najaflou, who also suffers from rheumatoid arthritis, has required hospital treatment twice since her injury, most recently for an infected surgical wound while remaining in custody, according to rights group Article18.

The sentences were issued on 21 October by Judge Abolghasem Salavati at Branch 15 of Tehran’s Revolutionary Court but were only communicated verbally to the Christians in late November and early December, the group said.

Judge Salavati was sanctioned by the United States in 2019 for his role in human rights abuses.

The Christians are expected to appeal, but advocates say the case reflects a broader pattern of punishing converts for peaceful activities such as worship, Bible distribution, and house-church meetings.

“The trial bore many hallmarks of a lack of due process: lengthy pre-trial detention, heavy bail demands, and the use of vague security-related articles to criminalize religious practice,” Article18 director Mansour Borji told Christian Daily International.

“Case files describe the distribution of Bibles and Christian texts, and efforts to share theology with others, as evidence justifying the sentences,” he added.

Under Iranian law, only ethnic Armenians and Assyrians born into Christianity are recognized as Christians; conversion from Islam is prohibited.

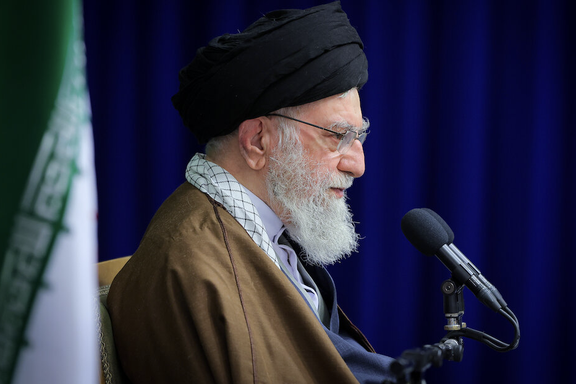

Free speech. Open dialogue. People having access to one another, the ordinary ability to speak freely and exchange ideas. These might be the downfall of the system patiently built up by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, not foreign weapons.

A public sphere not mediated by state television or controlled narratives. People simply talking to each other, in real time, in a forum beyond the reach of power.

That is the fear.

I say this not as a theorist or a politician, but as the host of a nightly call-in program that attempts, modestly and imperfectly, to make such exchanges possible.

The experiment is simple.

There are no slogans, no marching crowds, no images calibrated for cable news. Instead, there is a microphone, a live line, and an invitation so unassuming it almost sounds apolitical: talk. Not perform. Not chant. Not rehearse ideology. Just talk, to one another, in real time, about what has gone wrong, what hurts, what frightens, and what still feels imaginable.

A society that cannot speak to itself is condemned to repeat its errors. A society that can speak cannot be governed indefinitely by myth.

Fractured by fear

Iran is among the most politicized societies in the world, yet genuine political dialogue is structurally impossible.

Families learn which subjects to avoid at the dinner table. Schools train obedience rather than inquiry. State media speaks incessantly but listens to no one.

Even social media, often romanticized as a space of resistance, is fractured by fear, surveillance, and mutual suspicion.

The result is not apathy, but exhaustion.

Questions accumulate without resolution. Why does a country rich in oil and gas fail to provide reliable electricity? Why do rivers vanish while neighboring desert states manage water abundance?

Why does each generation inherit fewer prospects than the one before it? Is war inevitable? Is collapse? Is change possible without catastrophe?

These questions never cohere into shared understanding.

Online, coordinated campaigns flood debates with distraction and distortion, contaminating the very spaces where collective reflection might otherwise take shape. Fragmentation serves power.

A society arguing with itself is a society distracted from those who govern it.

The most dangerous conflict in Iran today is not between the state and the people, but among the people themselves, along ideological, generational and emotional fault lines.

In the aftermath of the recent brief war with Israel, many Iranians found themselves at a crossroads, unsure whether the future demanded silence, rupture, or something harder and more fragile.

Dialogue, in this context, is not reconciliation with power, nor a plea for moderation as a moral posture. It is not an elite exercise in rhetoric.

Real dialogue is untidy. It requires listening to voices one distrusts. It rests on a radical premise: that no one, neither the dissident nor the conscript, neither the exile nor the factory worker, is disposable by default.

The right to speak, and to hear

On my program, I try to create space for that premise to be tested. The format is open, live, and unfiltered. Callers speak without ideological vetting. What matters is not agreement, but participation.

Recently, callers from Tehran, Rasht, Shiraz and Zahedan spoke openly about leadership, foreign intervention, a monarchy versus a republic, internet shutdowns, nonviolent resistance and the ethics of accountability if the Islamic Republic falls.

Some urged speed. Others warned against vengeance. Some placed hope in figures abroad. Others insisted that change must be rooted domestically.

At one point, a caller argued that anyone associated with the state must be punished. Another responded that a society cannot be rebuilt on the promise of mass retribution. Justice, he said, requires distinction, between those who committed crimes and those who merely survived within a coercive system.

In most democracies, such an exchange would pass unnoticed. In Iran, it is revolutionary.

It is precisely this kind of public, imperfect, unscripted reasoning that authoritarian systems fear most.

The Islamic Republic today appears brittle. Its supreme leader speaks of progress while citizens search for medicine and hard currency. Parliament performs loyalty. The judiciary enforces obedience. State media manufactures fake optimism. Yet none of these institutions command belief.

What they cannot tolerate is unity that does not require uniformity.

A national conversation produces legitimacy, among citizens. It generates shared language, moral boundaries, and, eventually, political imagination. Once people agree on what the problem is, power loses its monopoly on explanation.

Speech connects. Connection organizes.

Silence, by contrast, is a slow death. It corrodes trust. It persuades people that their doubts are solitary.

They are not. Iran does not lack courage. It lacks space.

Every Thursday night, that space opens briefly on my show, long enough to remind people that the most radical demand is not vengeance, or even freedom, but the right to speak, to be heard, and to understand one another before history forces the conversation in blood.

That, ultimately, is what terrifies Iran’s supreme leader.

Former Israeli prime minister Naftali Bennett on Wednesday rejected a claim by an Iran-linked hacking group that it had infiltrated his mobile phone.

“Following tests that we conducted, it has been determined that Former Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s phone wasn’t hacked,” Bennett’s office said in a statement on Wednesday.

Earlier in the day, the group, calling itself “Handala” and linked to Iran’s intelligence ministry, alleged it had hacked what it described as Bennett’s iPhone 13 as part of what it called “Operation Octopus.”

It went on to publish a link it said reveals a trove of private communications it extracted from his device.

The name appears to reference Bennett’s own long-standing description of Iran as “the head of the octopus,” with regional allied militant groups as its arms.

In an open letter, the group taunted Bennett, writing: “You once prided yourself on being a beacon of cybersecurity ... Yet, how ironic that your own iPhone 13 has fallen so easily to the hands of Handala.”

“Consider this a warning and a lesson. If your personal device can be compromised so effortlessly, imagine the vulnerabilities that lurk within the systems you once claimed to protect,” the group added.

Handala published a series of files on its website and Telegram channel that it said were taken from the compromised device.

The group claimed it had gained access to private correspondence and contact information, publishing what it said were phone numbers linked to Bennett and to Avia Sassi, whom it described as a close associate.

Handala further claimed that the materials included private chats spanning several years, covering political coordination, candidate selection and, later, security-related concerns following the October 7 attack by Hamas militants on Israel.

Before the statement by Bennett’s office was released, Israel Hayom reported that Bennett’s office initially told the paper that it was "unaware of such an event." According to the report, Bennett’s security team said the matter is being handled by Israeli security and cyber authorities, that the device in question is not currently in use.

The report quoted Shai Nahum, a cyber warfare expert who reviewed the materials released by the group, said the data was unlikely to have originated from Bennett’s personal phone.

"According to forensic analysis of the leaked files, there is a high probability that this is not Bennett's phone, but apparently that of one of his associates," Nahum said.

Handala's claim comes a day after the group said it was offering a $30,000 reward for information related to Israel’s military sector after releasing material it said identified people involved in designing Israeli missile defense systems.

Who is Handala?

Handala is widely described by cybersecurity researchers and Western officials as tied to Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence.

It derives its name from a character created by Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali. A barefoot boy in patched trousers, Handala represented Palestinian dispossession.

Researchers say the group operates as part of a broader cyber unit known as Banished Kitten, also referred to as Storm-0842 or Dune, which they link to the ministry’s Domestic Security Directorate.

The group has been linked to cyber operations against Israeli infrastructure and public institutions for around two years.

In January, it claimed responsibility for a cyberattack on Israeli kindergartens that disrupted public address systems at about 20 locations. In August, the group was linked to hacks targeting multiple Israeli entities, including academic institutions, technology firms, media outlets and industrial companies.

Handala has also been linked to cyber operations targeting Iran International, a London-based Persian-language broadcaster.

Israel is reassessing the impact of its June military campaign on Iran’s ballistic missile program as analysts say Tehran is keen to rebuild its core deterrent in a move that could set the stage for renewed war.

Iran’s ballistic missile stockpile appears largely intact following the June war, with roughly 2,000 heavy missiles still in its arsenal, according to Al-Monitor.

The outlet cited an Israeli security source saying that Israel's military intelligence had conveyed the assessment to the United States in an indication that Israel is urging Washington to again act to address the alleged threat.

A senior Israeli official told lawmakers in a closed Knesset briefing, according to Israeli outlet Ynet, that large-scale ballistic missile production has resumed roughly six months after the June war.

“Iran is taking steps to rebuild its missile production capabilities," Greg Brew, Iran analyst with the Eurasia Group think thank, told Iran International," which is not surprising given that it is imperative for the regime to strengthen its position following the war in June.”

Brew said rebuilding missile capacity is a more likely near-term goal than reviving the country's stricken nuclear program, which would carry significantly higher political and military risks.

Iran's Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi said last month that Tehran had rebuilt its missile power beyond pre-war levels. Iran has also signaled its prowess publicly.

Last week, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps announced major naval exercises in the Persian Gulf involving cruise and ballistic missiles with a reported range of 2,000 kilometers, as well as suicide drones.

The critical question, analysts say, is whether Iran’s rebuilding efforts will be tolerated.

“The real question is whether these steps will be enough to trigger action by Israel,” Brew said. “I’m inclined to think that Israel will act preemptively to prevent Iran from rebuilding a missile arsenal that could theoretically overwhelm Israeli air defenses.”

Such a move would almost certainly require American backing, Brew added.

While Israel’s campaign inflicted significant damage, analysts note it was always constrained in its ability to impose lasting limits on Iran’s missile program.

Farzin Nadimi, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute said Israeli strikes hit at least 15 of Iran’s 30 to 35 main missile industrial complexes and about 15 of 25 missile bases, with numerous mobile launchers also targeted.

But Iran’s hardened underground infrastructure blunted the long-term impact.

“Considering the industrial basis and hardened nature of IRGC missile tunnel complexes, it is almost beyond doubt that original Israeli estimates of sustainable damage caused to those facilities is over-optimistic,” Nadimi told Iran International, referring to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Israel and the United States expressed public satisfaction at the impact their joint war in June dealt to Iran, while Iranian officials have insisted their capabilities remain intact and have vowed retaliation for any future attacks.

For Shahram Kholdi, an expert on Middle Eastern military history, the reassessment reflects a recalibration of expectations rather than strategic failure.

“The June strikes were aimed at degrading and disrupting Iran’s missile program at a critical moment, not eliminating it outright,” he said.

As Israel and the United States reassess Iran’s missile trajectory, question may no longer whether Tehran is rebuilding, but whether its progress will cross red lines that prompt preemptive action — and whether Washington would support it.

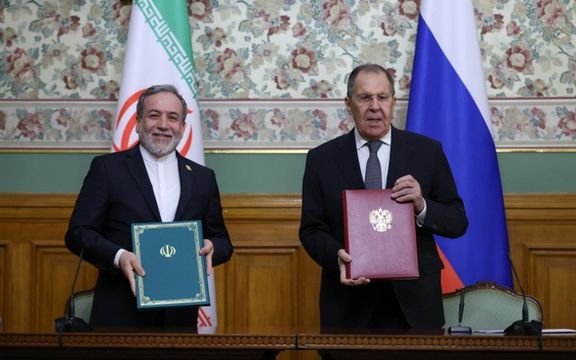

Iran and Russia signed a cooperation document between their foreign ministries on Wednesday after talks in Moscow, setting out a consultations program for the years 2026 to 2028.

The document was signed by Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov at the end of their negotiations.

Lavrov said the consultations plan was drawn up following the entry into force of a comprehensive strategic partnership treaty between the two countries earlier this year.

“Without any doubt, the main and key document in our relations is the comprehensive strategic partnership treaty between the Russian Federation and the Islamic Republic of Iran, which was signed this year and has entered into force,” Lavrov offering no details on the consultations agreement.

He said the treaty formally set out the special nature of bilateral relations and established key areas of cooperation and a long-term, 20-year outlook.

'Treaty deepens long-term cooperation'

The comprehensive strategic partnership treaty, signed in January by Russian President Vladimir Putin and Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian and ratified by both countries’ parliaments, commits Moscow and Tehran to closer cooperation across political, economic, security and technological fields.

While it does not include a mutual defense clause, the agreement provides for expanded military-technical cooperation, coordination on security issues, closer economic ties and efforts to reduce the impact of Western sanctions, including through financial and trade mechanisms outside the dollar system.

Lavrov said the signing of the 2026-28 consultations plan marked a first in the history of ties between the two countries.

“Today, for the first time in history, we are signing a consultations program between the foreign ministries of Russia and Iran for the years 2026 to 2028,” he said, adding that dialogue between the two ministries was regular and highly valuable.

Broader coordination under sanctions

Both countries have stepped up coordination as they face extensive Western sanctions. They cooperate in forums such as BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Eurasian Economic Union, and have expanded ties in energy, transport, trade, technology and space.

Iran and Russia say the strategic partnership treaty and the newly signed consultations plan provide a structured roadmap for advancing those ties over the coming decades.

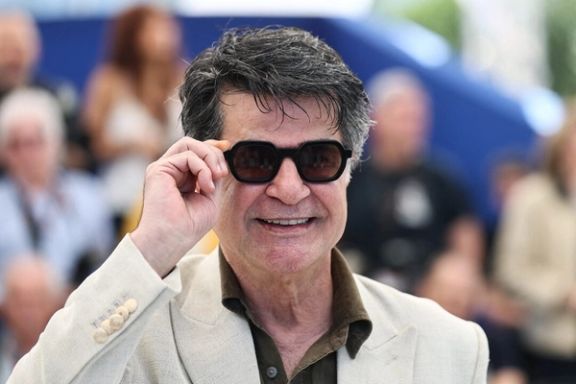

A film by dissident Iranian director Jafar Panahi has advanced to the shortlist for the international feature film category at the 98th Academy Awards, organizers said on Tuesday.

Panahi’s film, It Was Just an Accident, was included among 15 shortlisted titles as France’s official submission. Films from 86 countries were eligible in the category, with Academy members required to view all shortlisted entries to take part in the nominations round.

The film was made secretly inside Iran and follows the moral dilemma of a group of former political prisoners who believe they have captured the man who once tortured them. The work draws directly on Panahi’s own experiences of detention and surveillance.

It Was Just an Accident won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year, further cementing Panahi’s standing as one of Iran’s most internationally recognized filmmakers despite long-standing restrictions on his work.

Legal pressure at home

Earlier this month, Panahi’s lawyer said the director had been sentenced in absentia to one year in prison on a charge of propaganda against the state. The ruling also included a two-year travel ban and restrictions on political and social activity. The sentence was issued while Panahi was abroad promoting the film.

Panahi has said he plans to return to Iran after completing the awards campaign, despite the risks. “I have only one passport, the passport of my country,” he said earlier this month.

Oscar nominations will be announced on Jan. 22, 2026. The awards ceremony is scheduled for March 15 in Los Angeles.